|

|

The Life of Emma Octavia (Sexton) Strickler

(mother-in-law to Bill Hargiss)

Emma's parents:

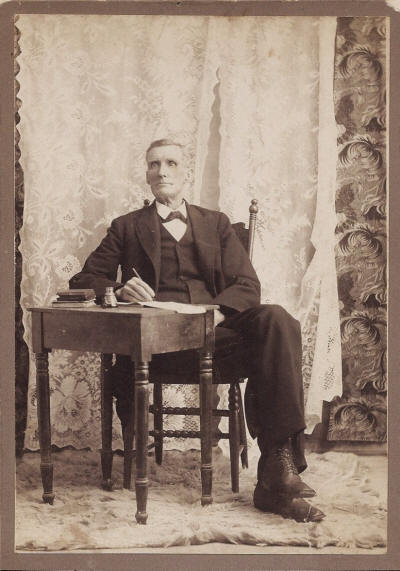

Franklin Clarke Sexton was born Feb. 24, 1832 in Macon, Georgia. He died Dec. 12, 1913 in Emporia, KS

Climelia Mauldin was born ca. July 5, 1832, in Lawrenceville, Georgia and died April 1, 1874 in Shelbyville, IN.

Franklin Sexton was married to Climelia Mauldin Jan. 12, 1853 in Gwinnet Co., GA.

They had three children: Joshua Glenn Sexton born 1854; Emma Octavia Sexton born July 4, 1856, Atlanta, GA; and Walter Alonzo Sexton born April 4, 1864 in Decatur, DeKalb Co. GA.

The following was written by granddaughter Genevieve Hargiss in 1983:

Emma Octavia Sexton was born July 4, 1856, in Lawrenceville, Georgia. All we know about her mother is that her maiden name was Climelia Mauldin and that

she died during Emma's early childhood. We know considerably more about her

father, Franklin Clarke Sexton. Emma, in her later years, had many stories

to tell about him; she had lived with him and cared for him throughout most of his

long life. He was an eccentric and a fanatic who was often a source of exasperation

to Emma. Yet she spoke of him affectionately, with humor and even a certain

kind of admiration and pride. We can get an idea of what he must have been

like by imagining a blend of John Brown and Carry Nation, with a keen intellect

and more reverence for the science of mathematics, in which he was self-educated,

than for the Lord God Jehovah of his time.

Franklin and his family lived in Decatur, Georgia, which was very

near Atlanta. We do not know how it happened that Emma was born in Lawrenceville.

Perhaps her mother's relatives were there. Emma had two brothers: Joshua (Josh),

who was older than she, and Alonzo (Lon) who was younger. From their house they

could hear the shelling and see the sky over Atlanta bright with the light from

flames during the siege of that city. In the midst of this was Franklin, a

rabid abolitionist and Union sympathizer who was not inclined to hide his feelings. In his own words, quoted by Emma, he was contemptuous of "hypocritical and cowardly

people who do not stand up for what they believe."

He had many skills with which he could have made a good living,

but he seemed to have very little concern about doing so. The small income

that he did have came mainly from his leather business. Tanning hides by hand,

he provided leather for a community that needed it but would not have bought it

from him had there been any other convenient way to get it. Although there

was a market for his product, Franklin worked only enough to feed his family. Apparently

he always managed to do this but sometimes just barely. He preferred to attend meetings,

quarrel with the Ku Klux Klan, and give vent to his anti-slavery passion at every

opportunity. Nevertheless, there came a time when he recognized that the better

part of valor was to flee the South.

When he left Georgia is not clear. He was still there at the end

of the war. Emma described women parading up and down the streets, waving their

aprons and cheering the news of Lincoln's assassination. Climelia had died.

Lon ran away, and Emma never heard from him or knew what happened to him.

This grieved her all of her days, as her younger brother had been the most important

person in her early life. Franklin and Emma moved to Shelbyville, Indiana,

and we do not know whether Josh had gone earlier, went with them, or followed later.

We do know that he settled in Indiana for a while because a newspaper account of

Emma's wedding in 1883 stated it took place in Indianapolis at the home of her brother,

J.G. Sexton. Soon after Franklin's arrival in Indiana, he began to express

his righteous wrath again, this time against the evils of alcohol. He was

still not disposed to work, but, consistent with his long-established pattern of

behavior, he did enough to support himself and Emma. We do not know much about

the kinds of work he did in Indiana, but he no longer tanned leather. He may

have been paid for some of his speaking engagements--he was not an ordained minister,

but he was certainly a preacher. He also tutored children of well-to-do families,

for which he was probably compensated. He continued to read and study literature,

history, and mathematics. He approved of Emma's determination to get a formal

education, and in his way he helped and encouraged her. She contributed increasingly

to her own support by taking various part-time jobs, including teaching in rural

schools before she was through high school. She was finally graduated from

Shelbyville High School at the age of 22. In 1878, a high school diploma conveyed

as much import, perhaps more, than a college degree in 1978, especially for a woman.

Emma immediately obtained a full-time position in the Shelbyville school system.

When he left Georgia is not clear. He was still there at the end

of the war. Emma described women parading up and down the streets, waving their

aprons and cheering the news of Lincoln's assassination. Climelia had died.

Lon ran away, and Emma never heard from him or knew what happened to him.

This grieved her all of her days, as her younger brother had been the most important

person in her early life. Franklin and Emma moved to Shelbyville, Indiana,

and we do not know whether Josh had gone earlier, went with them, or followed later.

We do know that he settled in Indiana for a while because a newspaper account of

Emma's wedding in 1883 stated it took place in Indianapolis at the home of her brother,

J.G. Sexton. Soon after Franklin's arrival in Indiana, he began to express

his righteous wrath again, this time against the evils of alcohol. He was

still not disposed to work, but, consistent with his long-established pattern of

behavior, he did enough to support himself and Emma. We do not know much about

the kinds of work he did in Indiana, but he no longer tanned leather. He may

have been paid for some of his speaking engagements--he was not an ordained minister,

but he was certainly a preacher. He also tutored children of well-to-do families,

for which he was probably compensated. He continued to read and study literature,

history, and mathematics. He approved of Emma's determination to get a formal

education, and in his way he helped and encouraged her. She contributed increasingly

to her own support by taking various part-time jobs, including teaching in rural

schools before she was through high school. She was finally graduated from

Shelbyville High School at the age of 22. In 1878, a high school diploma conveyed

as much import, perhaps more, than a college degree in 1978, especially for a woman.

Emma immediately obtained a full-time position in the Shelbyville school system.

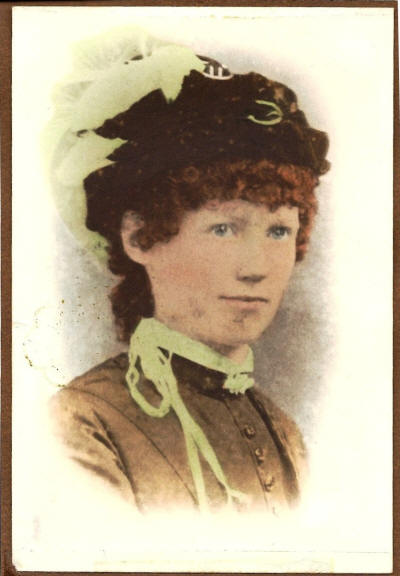

She had undoubtedly earned the respect of the entire community, and she now enjoyed a pleasant social, as well as academic, life. One of her friends, Martin Strickler, had a cousin way out in Kansas. In 1883 Tilghman Strickler came to Shelbyville.

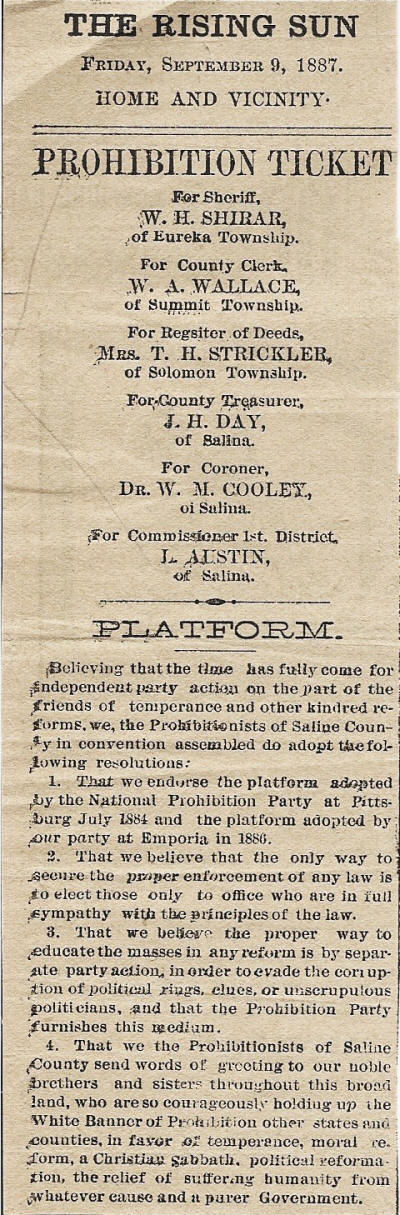

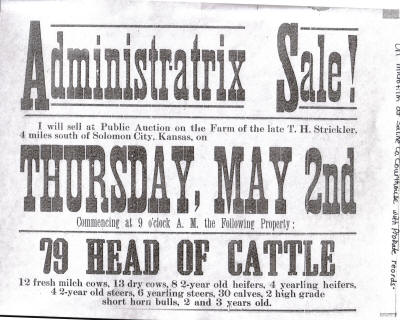

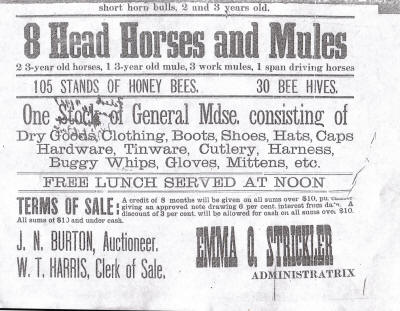

The following was printed in the Solomon Newspaper, 8/16/1903.

Franklin was not popular in the local community for his position favoring prohibition.

Old Man Sexton

In lookin' o'er the papers

That come from Shelbyville,

I see that old man Sexton

Is pokin' round there still,

An' makin' temprunce lectures

Jist like he used to do,

When clods an' clubs was plenty,

An' adled eggs wan't few.

Ur some place jist as far,

An' make a famous lecture

Agin the drinkin' bar,

An' then walk back that self same night,

Lay stone the followin' day,

An' never git a dog gone cent,

An' not expect no pay.

They called him almost ev'ry name

But gentleman, I think,

But still he hammered down their throats

His enmity to drink;

They called him fool, fanatic, crank,

"Old Long Back Sexton," too;

The more they raged an' cussed, and swore,

The firmer still he grew.

An' hated e're the wrong;

No sacrifice was great to him,

To help the cause along;

He never made no money,

Nur seemed to care ur know

Which side his bread was buttered on,

In this old world below.

He's more than eighty now,

Each year has left a furrowed mark

Upon that rugged brow;

I cannot tell what good he's done

When put to time's great test,

But this I can most surely say,

He's done his level best!

An' like as not some day

He'll slip into an unknown grave

With none to sing his lay;

No pillared shaft, perhaps, will rise

To mark the humble spot,

An', may be, in a few short years

The place will be forgot.

When Gabriel's day shall rise,

An' call us out o' earth and sea

To meet our last surprise,

'Longside o' many preachers,

An' salaried preachers too,

That this old man will stand up tall--

Jist like he used to do.

Emma meets and marries Tilghman Strickler:

Tilghman's grandfather, Samuel Strickler, came from England to

Shenandoah County, Virginia. We do not know the year of his arrival, but his son

Reuben was born there in 1796. A second son John, who was to be Tilghman's

father, was born in 1804 in Sullivan County, Tennessee.

Tilghman's grandfather, Samuel Strickler, came from England to

Shenandoah County, Virginia. We do not know the year of his arrival, but his son

Reuben was born there in 1796. A second son John, who was to be Tilghman's

father, was born in 1804 in Sullivan County, Tennessee.

Reuben and John migrated to Sugar Creek, Indiana, where they married sisters--Margaret and Susan Willard. These young women were descendants of Dewalt Willard who was born in Germany and came to America in 1746.

John Strickler's family Bible held entries of the births and marriages of his and Susan's descendants and also those of Reuben and Margaret. Sometime during the early 1950's the records of both lines were obtained by Vera Strickler Hargiss, Tilghman's youngest daughter. They are inserted in the back cover of the present book. Tilghman had an older brother named Samuel who is designated in the records as Samuel M. to distinguish him from their grandfather, the first Samuel.

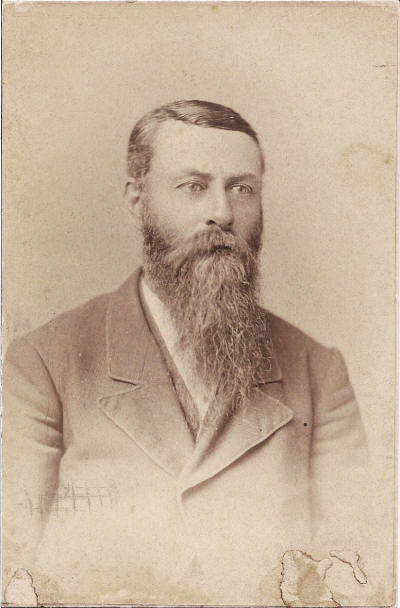

Tilghman was born in Shelby County, Indiana, May 5, 1840. He

began his working life as a miller and followed that trade until he joined the Indiana

State Militia in 1864. Later in the same year he went to Junction City, Kansas,

where he worked for his brother Samuel M. Strickler who was the junior partner in

the firm of Streeter and Strickler, government contractors in merchandising.

In 1868 he married Mary E. Blair and established a home and farm on the east half of

a section in Solomon Township in Saline County. He and Mary had two daughters: Flora

R.,

born in 1869, and Clarissa E., born in 1870.

Tilghman's wife Mary died Nov. 22, 1880. By that time Tilghman

was 40 years old and had begun to establish himself as an influential and well-to-do

"country gentleman." Through the years he had increased his estate, and now

he no longer farmed his land himself but leased most of it to others. He had

a large comfortable house with gas lights and running water. (The water was stored

in an outdoor tank and pumped by a windmill into the sinks and bathtubs.)

He had an orchard, an apiary, a cheese factory, and a general store. There

was a post office (Strickler, Kansas) in the store. There were stock barns, butchering

pens, an ice house; and a smoke house. There were also stables for the work horses

and carriage horses. There were several kinds and sizes of rigs for transportation

around the countryside or into town—to church, school, shopping, and various social

affairs. (Many years later, after Tilghman's death, Emma added riding horses

to the stables for the pleasure of her teenage daughter Vera and her friends.)

Back in Shelbyville, Indiana, one of Emma Sexton's friends was

Martin Strickler, a son of Reuben. He was Tilghman's double cousin. Martin

was one of eight children of Reuben, and Tilghman was one of seven children of John,

so there were still numerous Strickler relatives in Indiana when Tilghman visited

there in 1883. However, some had gone to Kansas as had Tilghman, and more

were to move there in the future.

We can only guess at the dynamics of Tilghman's visit to Shelbyville,

but we know the simple facts: Tilghman was looking for a suitable second wife.

Martin introduced him to Emma, Tilghman proposed marriage, and Emma accepted.

The wedding took place on October 15, 1883, in Indianapolis at

the home of Emma's brother Joshua. According to a newspaper clipping that

Emma saved, it was an important social event. The marriage certificate and

Emma's high school diploma are in the possession of her granddaughter at the time

of the present writing, 1983. We do not know whether Tilghman's daughters,

Flora and Clarissa, attended the wedding, but it is not likely that they did.

Nor do we know that there was any kind of honeymoon trip other than the journey

to Kansas.

Emma said that everything Tilghman told her before she married

him turned out to be accurate. He did not misrepresent his life style in Kansas

and what her part in it would be. He took it as a matter of course that her father

would live with them and graciously welcomed him to the Strickler household.

Emma had to have been a courageous and disciplined woman.

There were few options open to women in her time, and she was now 27 years old.

It may have seemed to her that Tilghman's proposal represented an opportunity for

security that would not come again. She neither romanticized nor dramatized

the situation, and she made a tough-minded decision. If she regretted it later,

no one ever knew.

Emma's life in Kansas was not easy, but it was probably not as

stressful or complex as we in later times may imagine. There were clearly drawn

guidelines that were recognized by the entire community. Roles were defined

and usually accepted without question. While such a setting was confining

and would be totally unacceptable to most women in the late twentieth century, it

did eliminate much of the confusion and anxiety we find in present-day living.

Emma said that Tilghman gave her sole authority when it came to managing the household,

including her step-daughters. Moreover, he made sure that this was understood

by all concerned. Emma had been a school teacher, and as such she had learned

the posture of a firm disciplinarian. She had no trouble with the girls or

with the household help. According to Clara, it was not long until they

all discovered that she was actually a soft touch when her heart was involved. By

that time they had come to love her, and the discipline was built-in.

Emma enjoyed the social position she had in her little world,

and the deference that went with it. She told us later that she knew she took

too much pride in this, but it is not hard to understand when we think of her early

life in a town that was hostile to her family.

She also liked to supervise the preparation and serving of the

meals in her home. Emma did not have to do everything that was required of

most farm wives, but it is interesting to consider what meal preparation meant on

the Kansas prairie in pioneer days. Vegetables had to be picked and canned;

fruits were canned or made into preserves or jelly. Grains were taken to a mill

to be ground into flour for making breads, pies, and cakes.

Cows were milked by hand. The milk was put in large open

crocks and left in the coolest place in the cellar for the cream to rise to the

top. Then the cream was skimmed off and most of it churned into butter. A

little of the cream was saved for the dining table--so thick it would hardly pour

from the pitcher. Some of the more enterprising farmers had ice boxes.

Ice that had been cut from the river in winter, packed in sawdust and placed in

an insulated closet in the cellar, would last through most of the summer and early

fall, depending on how hot the weather was in a particular year. This ice

was used only for cooling perishable foods and freezing ice cream; it was not put

into drinks. Drinking water was drawn or pumped from a well or cistern; some

farms had both. The well was a good place to chill melons by suspending them far

down into its depths. Slaughtering cattle and hogs was done by the men, either

the farmers themselves or hired help. In some areas there were itinerant butchers

who went from farm to farm. The meat was hung in a smokehouse to be cured

and/or dried, and it was left there until it was used. Lard was rendered from the

by-products. It was the women's job to trim and slice the hams and bacon as

they were needed, as well as to cook them. Feeding the chickens and gathering

eggs were in their province, and if there were turkeys and geese they took care

of those also. It was usually the young boys in the community who brought

in the fresh prairie game such as rabbits, pheasants, and quail. This gave

them a way to earn a little money (very little, like five cents for a rabbit).

Emma said that some farm women made their soap and candles, but

she did not. The lights in her house were gas and kerosene lamps. In the parlors

and dining room there were multiple lamps set into large chandeliers. She

remarked, incidentally, that the lamp chimneys had to be cleaned every day if they

were to be kept sparkling, and it was a very messy job. When she wanted candles

for atmosphere, she got them from Tilghman's store. The store provided her

with many items, some of which Tilghman obtained from neighboring farmers, either

by purchase or trade. There were a few things such as sugar, coffee, fancy soaps,

yard goods, and small tools that he arranged to have shipped in. Most of the

meats, poultry, fruits, flour, cheese, beeswax, and honey were produced on his own

farm. It was said that everything from a keg of nails to a pink chiffon veil

was available at the Strickler' store.

Emma apparently had her household so well organized that she could

be absent and know that the work, including the preparation of meals, would be carried

on smoothly. Most of the time, however, she was a close supervisor.

It was part of her credo that she would not ask any of her help (she never called

them servants, maids, or cooks) to do anything that she could not do and occasionally

did do, no matter how unpleasant. For example, the first step in the standard

procedure of preparing a chicken dinner was to catch the chickens and kill them

by wringing their necks. This was accomplished by holding the head of a chicken

in each hand, shoulder high, and whirling the birds around with a kind of cranking

movement of the arms until the bodies of the birds were severed from their heads. Emma did this sometimes, not so much to demonstrate how it should be done as to

promote the attitude that no honest and necessary work was beneath anyone's dignity.

Emma apparently had her household so well organized that she could

be absent and know that the work, including the preparation of meals, would be carried

on smoothly. Most of the time, however, she was a close supervisor.

It was part of her credo that she would not ask any of her help (she never called

them servants, maids, or cooks) to do anything that she could not do and occasionally

did do, no matter how unpleasant. For example, the first step in the standard

procedure of preparing a chicken dinner was to catch the chickens and kill them

by wringing their necks. This was accomplished by holding the head of a chicken

in each hand, shoulder high, and whirling the birds around with a kind of cranking

movement of the arms until the bodies of the birds were severed from their heads. Emma did this sometimes, not so much to demonstrate how it should be done as to

promote the attitude that no honest and necessary work was beneath anyone's dignity.

There were often extra persons at the Strickler dinner table.

Emma liked to do some of the actual cooking herself, and when only the family was

present she usually did it all. She had a talent for cooking and a reputation

for creating super menus. Mealtimes were occasions of leisurely family togetherness.

No one was permitted to hurry through, or be absent from, Emma's meals except for

extremely important reasons.

Another of her interests was the Women's Christian Temperance

Union. This was a strong organization in Kansas, and Emma did not need coaxing

to join its crusade. In this she found a kindred spirit in Clara. Together

they stumped their end of the state and spoke at rallies in churches, tents, town

halls--wherever an audience could be gathered.

Emma was very caring of both Clara and Flo, and she devoted much

time to them while they were still living at home. Clara was an extremely serious

girl. She wanted to attend high school and enlisted Emma's help in getting

her father's permission. It was soon forthcoming. She chose to go to

school in Chapman which was too far away for commuting by horse and buggy.

Arrangements were made for her to live with a family that Emma knew. However,

the railway train that went through Chapman (also Junction City, Abilene, and Salina)

would stop on signal at Solomon, not quite four miles from the Strickler farm.

So travel back and forth was not difficult. The high school at Chapman was

outstanding academically, and it still is. The present Dickinson County High

School continues to draw students from a wide area. In the lobby there is

a photograph of Clara's graduating class, one of the schools earliest. Only a short

time after her graduation she married a Methodist minister, Thomas Bear. They

lived in several small Kansas towns before the Reverend Bear died in 1916. He and

Clara had three sons: Paul, Newman, and Bruce. Clara went to Chicago with

Newman where she helped put him through medical school by managing a rooming and

boarding house. Vera and Genevieve visited her there in 1922. Then she

lived for a while with Paul and his wife Gerry and their three little girls, in

Elkhart, Indiana. Genevieve, "Mother Bear's niece," spent the summer there

in 1929. During the last years of her life, Clara had a small house of her

own in Riverside, California, where Newman was a physician. She died in 1961

at the age of 91. Almost her entire life was spent in service to her family

and to her church.

Flo was older than Clara although she did not seem so. She

had a lively, fun-loving, and outgoing personality. As a girl she was popular

with other young people, but she expressed no wish to go near a high school.

Emma said many times, in retrospect, that Flo kept the farm from being a dull place.

Clara was often indignant at her antics, but Emma was secretly amused. When

Flo put a large sign on the public road advertising hard cider for sale by Mrs.

Strickler, everyone was upset except Mrs. Strickler. More than 30 years later

she chuckled while telling about it.

Emma's sense of humor was her saving

grace; it undoubtedly helped her to weather some rough times. Flo had her

share of the rain that it is said must fall into each life. She married an

attractive ne'er-do-well and soon discovered that it was impossible to live with

him. It required great courage in that day to separate from him and establish

an in dependent life for her, but this is what she did. Divorce was unacceptable

even to her. She had her own millinery shop in Abilene and created her merchandise.

(The beautiful hats that Vera wore in some of her early photographs were made by

Flo.) After a while she moved her business to Hutchinson and was there for

many years raised the eyebrows of most of the good ladies around Solomon.

Clara had already frowned on her for abandoning her marriage, and now she was convinced

that the relationship in Hutchinson was an immoral liaison.

Emma did not believe

it for a minute. She continued to support Flo and defended her vigorously

when anyone dared to offer "sympathetic" innuendos. However, she was not able

to soften Clara's righteous anger. Clara felt that Flo had disgraced the entire

family, and she did not speak to, or write to, her sister ever again. They

both lived to be very old women without any kind of contact with each other.

Flo eventually became a Christian Science practitioner, as did Emma. We do

not know which one of them became interested first. Flo managed a Christian

Science sanitarium, Mount Tabor, in Portland, Oregon. Emma spent two years

with her there in the 1920's. (Genevieve visited her in Oregon in 1940, but

she was no longer at Mount Tabor.) Flo had adopted two little orphan girls,

but one of them died very young. The other became a career woman and attained

an executive position with the Northwestern Bell Telephone Company. Flo's

husband had long been deceased, and she married again in Oregon after World War

II. She and her second husband retired to Wecoma Beach. Vera went to see both

Flo and Clara in 1953, hoping to reconcile them. Her efforts were not successful.

We had a long letter from Flo, and also one from Clara, when Vera died in 1955.

We heard from Flo for the last time in 1961. We do not know how much longer

she lived after that; her husband did not inform us of her death.

Emma's sense of humor was her saving

grace; it undoubtedly helped her to weather some rough times. Flo had her

share of the rain that it is said must fall into each life. She married an

attractive ne'er-do-well and soon discovered that it was impossible to live with

him. It required great courage in that day to separate from him and establish

an in dependent life for her, but this is what she did. Divorce was unacceptable

even to her. She had her own millinery shop in Abilene and created her merchandise.

(The beautiful hats that Vera wore in some of her early photographs were made by

Flo.) After a while she moved her business to Hutchinson and was there for

many years raised the eyebrows of most of the good ladies around Solomon.

Clara had already frowned on her for abandoning her marriage, and now she was convinced

that the relationship in Hutchinson was an immoral liaison.

Emma did not believe

it for a minute. She continued to support Flo and defended her vigorously

when anyone dared to offer "sympathetic" innuendos. However, she was not able

to soften Clara's righteous anger. Clara felt that Flo had disgraced the entire

family, and she did not speak to, or write to, her sister ever again. They

both lived to be very old women without any kind of contact with each other.

Flo eventually became a Christian Science practitioner, as did Emma. We do

not know which one of them became interested first. Flo managed a Christian

Science sanitarium, Mount Tabor, in Portland, Oregon. Emma spent two years

with her there in the 1920's. (Genevieve visited her in Oregon in 1940, but

she was no longer at Mount Tabor.) Flo had adopted two little orphan girls,

but one of them died very young. The other became a career woman and attained

an executive position with the Northwestern Bell Telephone Company. Flo's

husband had long been deceased, and she married again in Oregon after World War

II. She and her second husband retired to Wecoma Beach. Vera went to see both

Flo and Clara in 1953, hoping to reconcile them. Her efforts were not successful.

We had a long letter from Flo, and also one from Clara, when Vera died in 1955.

We heard from Flo for the last time in 1961. We do not know how much longer

she lived after that; her husband did not inform us of her death.

Emma's children:

On Sept 30, 1884, Emma gave birth to the first child of her own.

Roscoe was a husky baby, but he died after a sudden and short illness when he was

only 18 months old, May 16, 1886. Emma did not tell us much about this experience except

to say that it was especially hard for her husband. A son was about the only

thing left that he wanted and did not have.

Vera, Emma's second and last child, was born

Jan 15, 1888—another daughter

for Tilghman. However, his disappointment, if he felt any, did not last long.

This little girl, in the eyes of her father, was the golden-haired princess of the

storybooks.

Vera, Emma's second and last child, was born

Jan 15, 1888—another daughter

for Tilghman. However, his disappointment, if he felt any, did not last long.

This little girl, in the eyes of her father, was the golden-haired princess of the

storybooks.

Emma and Tilghman did something in 1894 that turned out to be

unfortunate. There must have been a reason, but we do not know what it was.

They took a four-year-old boy to raise. The family into which he was born

had more children than they could feed, and they simply gave the one named Ellsworth

(Eldie) to the Stricklers. Such a transaction was not uncommon in those days;

usually, as in this case, there was no legal adoption. Although Ellsworth

took the Strickler name, he was not a Strickler and no one treated him as a Strickler.

No doubt Emma and Tilghman had good intentions, believing that it was kind and charitable

to feed, clothe, and shelter a child who might otherwise have starved. At

the end of the nineteenth century, only a few people understood how important it

is to the healthy nurturing of a child that he be given a feeling of belonging and

helped to develop self-esteem. Ellsworth was deprived of these, and it is very likely

that he had a weak genetic inheritance to begin with. We cannot wonder at

his becoming an unhappy and incompetent person.

Tilghman dies:

Tilghman died Jan. 27, 1901 at the age of 61, supposedly because of

a heart attack. However, about a month earlier an irate man had come into

the store wearing brass knuckles and bent on revenge for what Emma said was an imagined

wrong. He gave Tilghman a blow on the head that knocked him unconscious.

Emma was convinced that this had some connection with his death; there was no history

of heart attacks in his family as far as she knew.

Emma was a widow at the age of 44. The size of Tilghman's

estate has never been clear to her grandchildren. Presumably it all went to Emma,

but she had very little of it left 10 years later. She did not have the skills

nor the temperament to carry on her husband's many enterprises. She began

to sell them, little by little, and there is no doubt that some people took advantage

of her need to do so.

She sent her daughter Vera to a private girls' school in Liberty,

Missouri, and then to the Salina (Kansas) High School when she was ready for it.

Emma encouraged her to bring her Salina friends to the farm for house parties during

weekends and holiday so Mother and daughter took several trips together, including

vacations in Indiana where they renewed contacts with relatives

The farm suffered a severe loss in 1905 when Eldie tipped over

a kerosene lantern in the main barn. The fine large structure burned to the

ground. Some of the horses were rescued but not all. They had to be

blindfolded and led out one by one.

Emma moves to Emporia:

We think it was in 1906, or perhaps 1907, that Emma sold all of

her remaining holdings and moved to Emporia where Vera wished to study music at

the conservatory there. Her father Franklin went with them. She either

loaned or gave Eldie the money to buy a small farm in southeastern Kansas about

four miles from the town of Fredonia.

We think it was in 1906, or perhaps 1907, that Emma sold all of

her remaining holdings and moved to Emporia where Vera wished to study music at

the conservatory there. Her father Franklin went with them. She either

loaned or gave Eldie the money to buy a small farm in southeastern Kansas about

four miles from the town of Fredonia.

In Emporia, Emma leased a large Victorian house on 12th Street,

about where the Emporia State University Music Hall was to stand many years later.

When Emma went there, this school was called the Kansas State Normal. She

ran a boarding club for students and faculty, serving dinners at noon and suppers

in the evening. Franklin enjoyed the students, especially those who were taking

mathematics courses. He liked to argue with them about the problems they were

assigned to do outside of class and often confounded them by demonstrating alternative

ways to reach the same solutions

In Emporia, Emma leased a large Victorian house on 12th Street,

about where the Emporia State University Music Hall was to stand many years later.

When Emma went there, this school was called the Kansas State Normal. She

ran a boarding club for students and faculty, serving dinners at noon and suppers

in the evening. Franklin enjoyed the students, especially those who were taking

mathematics courses. He liked to argue with them about the problems they were

assigned to do outside of class and often confounded them by demonstrating alternative

ways to reach the same solutions

It was sometime during this period, we do not know precisely when,

that Emma became acutely ill and underwent surgery to remove gallstones. Shortly

afterward she began to read Christian Science, and Vera became interested too.

This religion was of great consequence to both of them for the rest of their lives.

Emma was separated from her daughter when Vera was graduated in

1909 and went to Halstead, Kansas, to teach music and German. She was there only

two years, however, and came back to Emporia in the summer of 1911 when she married

Bill Hargiss. They lived in a small house on the western edge of town.

In the meantime Emma's house was commandeered by the State Normal

School, and the land was added to the campus. She moved to a similar house on Merchant

Street where she continued to operate her boarding club. During one of the

school vacations, when most of her boarders were away, she went to Kansas City for

the instruction that qualified her to be a Christian Science practitioner.

Franklin dies and Emma moves to Oregon with Vera:

In 1913 Franklin traveled to Shelbyville, Indiana, to see his relatives. There were not many left whom he knew, and he found the visit depressing. He soon returned to Emporia and died a short time later, probably in 1914. Emma had never lived alone, and it was difficult for her at first. She tried living with Eldie on his farm near Fredonia, but neither of them was happy with this arrangement. When Bill and Vera moved to Oregon in 1918, Emma went with them. Eldie was disgruntled because his farming venture was almost a total failure, so he wandered to California. It was wartime, and he was able to get a job with the Pacific Electric Railway Company as a train conductor. He had been required to register for the draft, but he was rejected because of his poor physical condition. Vera's husband Bill had also registered, but he was deferred because his work with student athletes was considered to be in the national interest.

In Corvallis, Oregon, Emma did not live with Vera and Bill but

rented a small apartment over a motion picture theater. She turned her front

room into an office and hung up her shingle as a Christian Science practitioner.

She was more contented now than she had been for some time. She had the companionship

of the older women in the church and also that of a bereaved man or two. Her

stepdaughter Flo lived in Portland, and they exchanged visits. Vera and Bill

had two children; Emma often served as their sitter, a job at which she was superb.

This pleasant life in Oregon ended with the illness and death

of the younger child in 1920. Bill had decided to return to Emporia and went

to Kansas early in the summer to recruit athletes, for the fall semester, leaving

the rest of the family to oversee them packing and moving. The child died in August.

Sixty years later Genevieve remembered the sound of Emma's voice and her words that

were almost a whimper: “I have had each of my bad experiences twice." To what

she was referring, in addition to losing her baby son Roscoe, we do not know.

Emma did not stay long in Kansas this time. She and another

Christian Science practitioner had been thinking about going to California together,

and now, after her grandchild's burial in Emporia, Emma went with her friend to

Long Beach. They leased a house on the ocean front and used part of it as

offices for joint practice. They also set aside a room for Eldie, who at that time

was working the interurban run between Long Beach and Los Angeles.

Emma was just beginning to have a few patients when she fell and

broke her hip (or perhaps her hip broke and this caused her to fall). She

was not able to leave her bed for many weeks. Vera spent most of the summer of 1921

caring for her in Long Beach. Her nine-year-old daughter went with her because

there was no one with whom she could be left. Emma's practitioner friend wanted

out of the partnership, and when it was time for school to begin in the fall and

Vera had to return to Kansas; Emma was not yet able to take care of herself.

Vera brought her back to Emporia. (Emma never recovered fully from her injury.

She lived another 15 years, and in all of that time she could take only a few steps

without crutches or sturdy canes.)

The following summer (1922) Emma was able to go with Vera and

Genevieve to Evanston, Illinois. They lived in a rented apartment, Emma doing

the cooking and looking after Genevieve--her granddaughter who was now 10 years

old. Vera studied voice and worked part time for Cyrus Kitching, a well-known

percussion instrument maker. (His heirs were still building much-sought-after Kitching

instruments over 50 years later.) Emma's stepdaughter Clara was managing a

rooming house on the south side of Chicago while her son was in medical school.

She and Emma saw each other several times that summer.

The next year Emma went to the little town of Fredonia, Kansas,

where she had some friends, and resumed her Christian Science practice. Genevieve

made frequent visits there, sometimes staying for a month or more.

Emma's stepdaughter Flo was now the manager of Mount Tabor, a

Christian Science sanitarium near Portland, Oregon, and for some time she had been

asking Emma to come there and help her. Finally in 1925, the invitation was

so insistent that Emma pulled up stakes in Fredonia and went to live with Flo.

Again, it seemed that an unlucky star followed her--the next year she became very

ill. Flo told us afterward that she tried to assure Emma of loving care as

a patient in Mount Tabor, which by all accounts was a beautiful place. Nevertheless

Emma wished to go to Vera, and she made the long journey by train, all by herself.

She was quite ill for over a year, and this was the first time she had lived with

Vera and Bill since their marriage. By now there were two more children besides

Genevieve; Emma was the sixth person living in their small house. It was a

bad time for both Emma and Vera.

When the family moved to Lawrence in 1928, Emma was well enough

to live alone again. In Lawrence she took rooms over a store in the downtown

area, which she thought would be a good place for a practitioner's office.

There was no elevator, and the long, steep stairs were so difficult for her that

she seldom went out. Vera took her to church on Sundays and usually brought

her home to spend the rest of the day with the family. Also, people came to

her rooms to see her; she had some patients as well as several friends in the church.

Genevieve visited her often and shopped for things she needed. She ordered

her groceries by telephone, and they were delivered the same day.

Emma lived six and one-half years after coming to Lawrence.

Vera and Bill brought her to their house for the last three months of her life;

she died there January 21, 1935. Her last words were, "Now I must get more

harmonious."

Emma was not a restless wanderer, nor was she a complainer. Apparently

her basic nature was happy, and there was no self-pity or hostility in her.

She may have saved herself from a pathetic and lonely old age by her interest in

others and also by her sense of humor--it was irrepressible and sometimes subtle,

but it stayed with her until the end.